In 1748, the British aristocrat John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich, loved playing cards. He loved playing so much that he seldom stepped away to eat.

So he came up with the idea to eat beef between slices of bread, which would allow him to eat and play cards at the same time. Fellow card players saw what he was doing and began to adopt the habit – telling the Earl’s servants they would like to order a “sandwich.”

The concept has become one of the most popular meal inventions in the western world.

And now you are likely to never forget the story of how the sandwich was invented.

Stories make information understandable and memorable

Storytelling has been with us as long as there have been people – well probably. A couple thousand years ago Aristotle wrote advice on how to tell a story: it should have a beginning, a middle and an end. It should include a variety of realistic characters, some of whom suffer at least one reversal of fortune. Good advice.

There is an infographic making the rounds on social media right now which attempts to explain the science to why storytelling is so powerful. It was featured recently in the New York Times which is probably why it’s being popularized on social media sites right now.

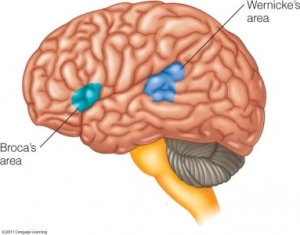

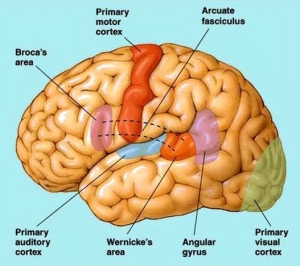

Basically, if we read a report or sit through a PowerPoint presentation with boring bullets only two areas of our brain get activated. Scientists call these Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area. Overall, the information reaches our language processing parts in the brain, where we decode words into meaning. And that’s it, nothing else happens.

Basically, if we read a report or sit through a PowerPoint presentation with boring bullets only two areas of our brain get activated. Scientists call these Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area. Overall, the information reaches our language processing parts in the brain, where we decode words into meaning. And that’s it, nothing else happens.

When we are being told a story, though, things change dramatically. Not only are the language-proce ssing parts in our brain activated, but up to seven regions flicker with light and activity.

ssing parts in our brain activated, but up to seven regions flicker with light and activity.

If someone tells us about a great song they heard on the radio our auditory cortex lights up. If it’s about motion, our motor cortex triggers.

Write a story that says the singer had a raspy voice and leathery hands that clasped the microphone tightly and we don’t just have mental image – we are virtually experiencing the story.

There’s real science to this. Researchers in Spain have found that narrative is infinitely more powerful than messages or facts.

Cognitive science has long recognized narrative as a basic organizing principle of memory. From early childhood, we tell ourselves stories about our actions and experiences. Accuracy is not the main objective – coherence is. If necessary, our minds will invent things that never happened simply to hold the narrative together.

Stories that are personal and emotionally compelling engage more of the brain, and thus are better remembered, than simply stating a set of facts.

How can we use this as communicators?

-

Use Story – stories that are personal and emotionally compelling engage more of the brain and thus are better remembered than simply stating the facts

-

A Key Message approach is ok but your messages need to describe a broader narrative – not just convey statistics and information

-

When someone asks what your company does, do you tell them what you do? Or why you do it? Why is always more engaging than what.

-

Make sure your stories are the right kind of story for your audience and your circumstances. Make them believable

-

Make sure your story is tightly structured. Without structure – you’re just talking

-

Let your audience do some of the emotional work for you. The shortest story ever written was just six words and does a great job of making people think “For sale: baby shoes, never worn”

| Storytelling | Just the Facts |

| Stories activate multiple senses in the brain; motor, auditory, olfactory, somatosensory and visual | Facts activate two parts of the brain – Broca’s and Wernike’s areas |

| Stories use words that spark the senses making it easier for the brain to imagine, elaborate and recall. Each person develops their own unique experience from these experiences | Facts use abstract, conceptual language that is more difficult for the brain to find associated sensory images |

| Stories are easier to recall due to the power of their sensory associations | Facts are difficult for the brain to record and remember. This is why acronyms are popular because they help recall |

| Stories create characters we can identify with | Facts don’t create characters and don’t generate emotional associations |

| Stories invoke emotion which is a neural activator. Emotional associations trump other forms of processing | Facts are difficult to recall without emotion |

| Stories come in recognizable sequence – introduction, rising action, climax, falling action | Facts are more linear and don’t easily form a recognizable temporal sequence |

| Stories provide motivation for action | Facts are not inherently motivational unless knowing about something has additional benefit to us in terms of our ability to survive or thrive |